The term cantorial “golden age” signals a period of mediatization and popularization of Ashkenazi liturgical music in the transnational Yiddish-speaking Jewish community from roughly the last decade of the 19th century to the decade following the Holocaust. In this period cantors moved ritual music out of synagogue spaces and into the newly emerging media sphere of concert stages, Yiddish theater, radio and, most crucially for the emergence of new practices of sacred listening, the gramophone record. Cantors of the golden age offered a model of a new form of Jewish personhood: an artist who moved between worlds of aesthetic achievement, performance, sensual pop culture iconography, engagement with the burning political ideologies of the period, and sacred authority.

My proposed second book project I am currently at work on, Melody Like a Confession, will constitute the first monograph on the cultural history of the transnational gramophone era cantorial phenomenon. This proposed book project will bridge archival research, ethnomusicological analysis, and a cultural studies approach steeped in the fields of performance studies and comparative literature. The project is premised on the view of cantorial music as both a form of expressive culture and an intellectual movement within a rapidly evolving period of social change and cultural reinvention. Cantorial music, in the eyes of its key practitioners and their critics on both sides of the Jewish Atlantic world, offered a populist response to modernization, state violence, and migration.

In my previous dissertation research and book project, titled Golden Ages: Hasidic singers and cantorial revival in the digital era, I offered an ethnographic study of young singers in the Brooklyn Hasidic community who look to the cantorial golden age for the stylistic basis of their own aesthetic explorations. In my book I propose a view of their work as a non-conforming social practice within the conservative contemporary Hasidic community. Hasidic cantors call upon the sounds and structures of Jewish sacred musical heritage to stage a disruption in the aesthetics and power hierarchies of their community. Beyond its role as a desirable art form, golden age cantorial music offers a model for aspiring Hasidic singers of a form of Jewish cultural productivity in which artistic excellence, maverick outsider status, and sacred authority were aligned. The work of these contemporary cantors offers clues about the meaning of the work of gramophone era cantors, suggesting that these historical figures offer a precedent for musical and social practices that defy institutional authority and push at normative boundaries of sacred and secular by foregrounding artist’s voices in the culturally intimate space of prayer.

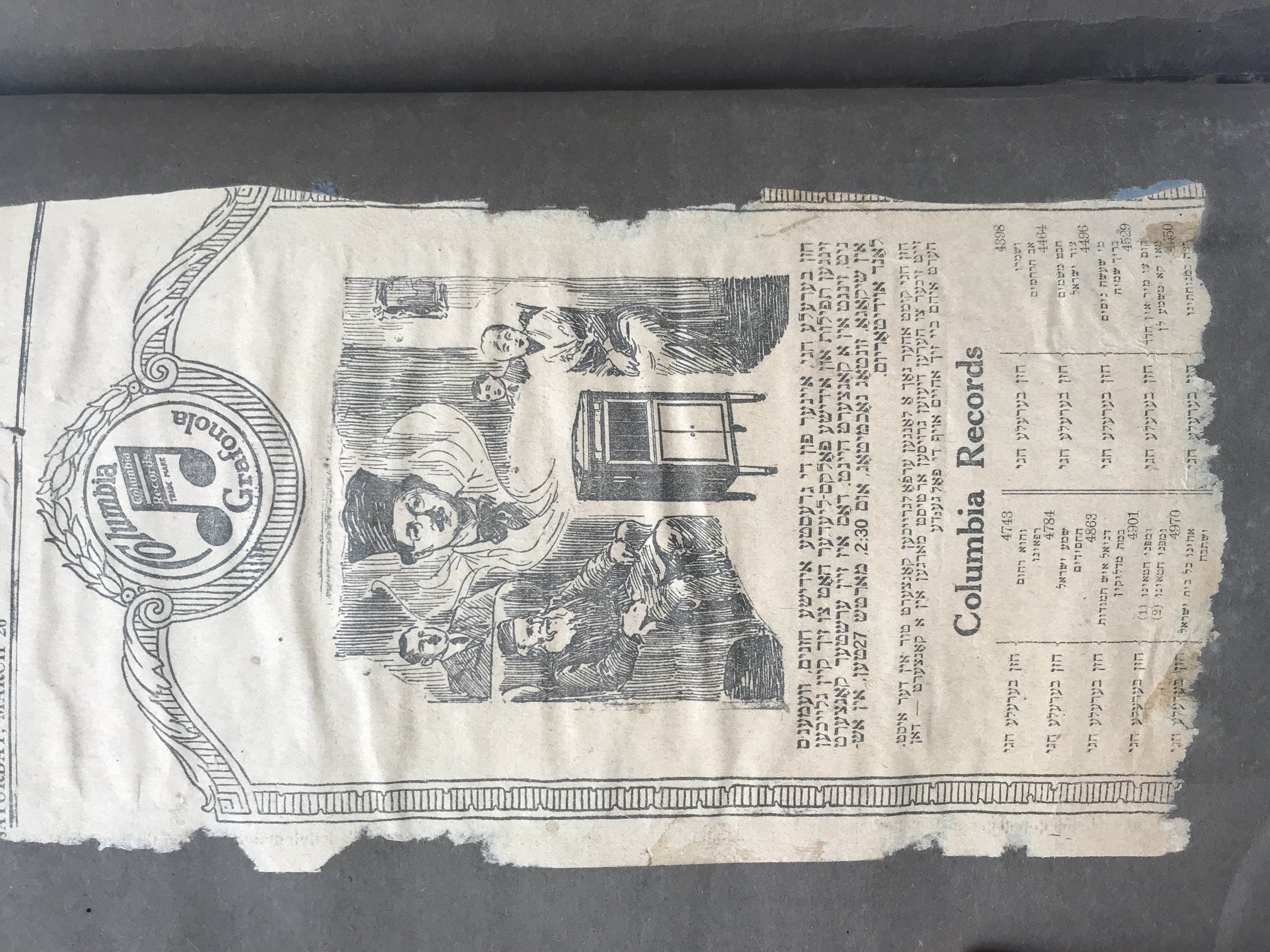

I intend for my further research on “golden age” cantors to amend a lacuna in modern Jewish cultural history and contribute to broader interventions that advocate for a view of artists and aesthetics as needed elements in constructing histories of marginalized communities. Pursuing archival research about gramophone era cantors, I have made preliminary findings in the Yiddish press that suggest cantors were founts of passionate controversy, aesthetic partisanship, and fulcrums of communal fundraising and organizing in the immigrant community in the United States. Cantors and their critics debated the appropriateness of sound recording, performance outside of the synagogue, and the commercialization of the sacred. These themes in the cantorial sphere paralleled discussions among Yiddish authors about the dialectical role of literature and theater as forms of intellectual cultivation versus their potential impact as a degrading form of populism. Cantors engaged in cultivating a conception of Jewish memory that pivoted between nostalgic images of an imagined Jewish folkloric past and appeals to the ineffable and transcendent in music that would establish a Jewish aesthetic parallel to the achievements of European classical music. These aesthetic claims run parallel to contemporary Jewish political movements that pivoted between nationalism and socialism.

Artists in the cantorial market were often considered “outsiders” because of their lack of rabbinic pedigree or economic elite status. Cantorial stars were at times reviled by conservative critics for their lack of adherence to norms of religious orthodoxy, even as they were subjects of public adulation. The emergence of new media opened cantorial performance to artists with controversial identities, including women cantors, often referred to in Yiddish as khazntes. The khaznte phenomenon, that seems to have begun in the 1910s, brought women cantors to the forefront of popularity, even as they were rejected as ritual leaders in synagogues. The study of the cantorial golden age will bring these important yet forgotten artists into the light of day and reevaluate the gendered history of liturgy and aesthetics by attending to their work.

Melody Like a Confession will address the central themes of the cantorial populist movement in thematically organized chapters. I have already completed a draft of a chapter on the khazntes, early 20th century women cantors. I have developed a prospectus and research agenda for the other chapters of the book. The proposed chapter are: an introduction that will offer a synthetic approach to the representation of cantors and their music in the Yiddish press and literature; a chapter focusing on the political commitments of cantors and their pivotal involvement as ideologues and fund raisers in labor union politics and Zionism; a chapter that will focus on the culture of chastisement and the ethical ambiguities that surrounded cantors as both preservers of sacred heritage and pop culture stars; and a final chapter that will look at the reception of the cantorial gramophone era in its various “afterlives” across the 20 th and 21 st centuries. This work will present an important reparative to the dearth of serious scholarship on an era that is referred to as a “golden age” and that plays an outsized and highly mythologized role in the conception of Jewish musical heritage. By placing cantors in dialogue with Yiddish literature and Jewish political movements, I will move the discussion of Jewish sacred music out of its current highly parochialized place and cultivate a more robust approach to this pivotal intellectual and aesthetic movement in Jewish life.